.com

Estd. 2020

Centenary

Project

2027

Approved by the Shaw Family

TOMORROW

AT TEN

"I know it ticks, it's special."

"I wanted to be just like him." - Ian Shaw

trailer

Robert Shaw as George Marlow

It's a race against time for the police when they have to find a kidnapped boy imprisoned with a time bomb, after his abductor dies without revealing the child's whereabouts.

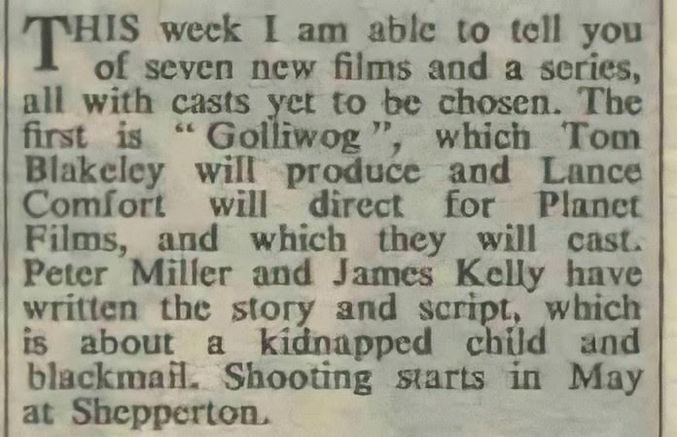

Directed by Lance Comfort

Screenplay by James Kelley and Peter Miller

Produced by Tom Blakeley

Music by Bernie Fenton

Cinematography by Basil Emmott

Edited by John Trumper

Also starring John Gregson, Alec Clunes, Kenneth Cope, Alan Wheatley, William Hartnell, Betty McDowall and Helen Cherry

Released by Mancunian Films

Release Date: June 23rd 1963

Running Time: 80 minutes

Location(s): MGM Studios Borehamwood and London

Filming commenced: June 12th 1962

gallery

TOMORROW

AT TEN

Official Movie Soundtrack

Main title and end credits composed by Bernie Fenton.

Italian Version

Full Movie with Italian subtitles.

TOMORROW

AT TEN

Press Play

TOMORROW

AT TEN

DIRECTOR

Lance Comfort

(1908 - 1966)

John

Gregson

(1919 - 1975)

Alec

Clunes

(1912 - 1970)

Helen

Cherry

(1915 - 2001)

William

Hartnell

(1908 - 1975)

Alan

Wheatley

(1907 - 1991)

Betty

McDowall

(1924 - 1993)

Kenneth

Cope

(1931 - 2024)

This is where we see the beginnings of the great movie villain that Shaw was to become in this British B thriller.

Shaw is mesmeric as Marlow, who kidnaps a young boy and plants a timer bomb in a toy as he tries to extort money out of wealthy businessman Anthony Chester. Robert gives a quietly brooding performance in a cockney accent and the only sad thing is he's only in half the film.

The tension lasts until the final reel as the clock ticks down. John Gregson is excellent as the dogged detective who works through the night to find and save the child.

It's well made with a good ensemble cast and script and is perhaps the first real meaty role Shaw had in his film career and he pulls it off with flying colours.

Lobby Card Gallery

TOMORROW

AT TEN

On its release in the summer of 1963, Tomorrow at Ten received the lukewarm reviews usually accorded to a low-budget film noir of the period. However, watched now in context of other films of the genre, it does have notable elements which set it apart.

Tension is powerfully established during the pre-credits sequence and built up throughout, especially in the intercutting between young Jonathan locked in the nursery and the police attempts to find him. The barely disguised panic and frayed tempers of the adults contrast with the boy's calm demeanour.

The film transcends the usual kidnap scenario by having the kidnapper confront both the father and the police, lending the conflict an extra dimension. Moreover, the death of Marlowe and the failure of the police to rescue Jonathan in time subvert generic expectations.

The air of antagonism is exacerbated by the lack of female characters: Jonathan's mother is absent, the nanny serves little purpose, save calling the police, after the kidnapping occurs and Parnell's wife waits at home with the dinner on the table.

The film is heavy on dialogue and shows a greater interest in psychology than most second features, though it is hindered by time and budget restrictions which allow little development of character and motivation.

The character of Parnell is rather one-dimensional, defined by his tenacity and belief in his own ability to persuade others to open up to him; beyond this, the film fails to offer much insight into his personality. The character of Marlowe is also somewhat subservient to the plot; tellingly, Parnell is on the point of discovering the root of his anger, but Marlowe dies before revealing his motive.

Headed by two experienced and charismatic actors, Robert Shaw and John Gregson, Tomorrow at Ten is a more convincing affair than many such low budget programme fillers, although Shaw was yet to reach the peak of his fame.

Other guest stars beef up the smaller parts, with William Hartnell and Renée Houston playing Marlowe's parents. Their one scene takes place in the seedy club they run, with its Afro-Caribbean man playing the bongos and buxom woman gyrating to the exotic beat, and is typical of films of the period in focusing on the underbelly of life in the city, anticipating the 'swinging London' period about to explode.